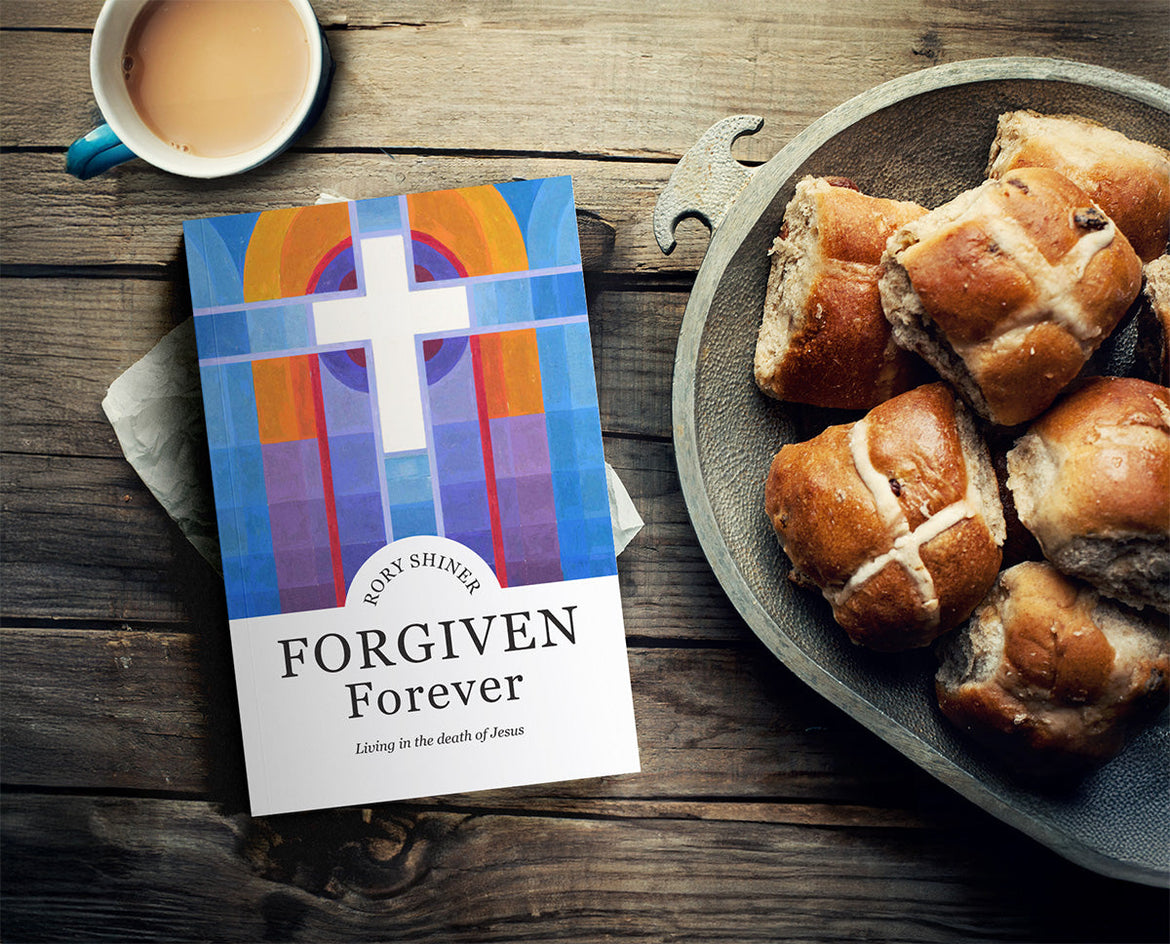

Excerpt from Forgiven Forever

This Easter we would love to share with you a passage Rory Shiner wrote as part of Forgiven Forever, his book that explores the relationship between Jesus’ death and daily Christian living. May you be encouraged like we were!

Facing the dragon

From Forgiven Forever by Rory Shiner

In The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins must enter a cave, confront a dragon, and fulfil his mission. As is often the case in a hero’s quest, he must confront his own fear before confronting the enemy itself. Indeed, the confrontation with the enemy itself is often not nearly as challenging as the prior decision to keep moving towards that moment of confrontation. “Going on from there was the bravest thing he ever did.”*

Jesus has precisely this sort of moment. He has it in the garden of Gethsemane, the garden of tears. This is Jesus’ “cave”—the place in which he confronts the dragon and takes perhaps his most important step towards fulfilling his mission.

Jesus in the Garden was a ‘problem passage’ for the early church. From the very beginning, Christians have insisted that Jesus is God: God become man, God incarnate. But if that’s true, then what’s happening here in the Garden? A God who prays? A God who asks that God’s will be done? A God who is anxious and afraid? How does that even work?

For many, the scene in Gethsemane was proof positive that Jesus wasn’t God. Perhaps he wasn’t even a great man. Jesus is not the first man to face his death, of course—it comes to us all, and most of us fear it to some extent. But many people—whether religious or not—face their death with dignity and courage. Jesus, on the other hand, faces his death with an apprehension that many others seem to avoid.

You’ll recall, Jesus is not facing the ravages of cancer or ageing—awful though those are. He’s a leader, a prophet—a man about to be killed for what he believes in. He’s not the first such leader. In the very recent history of Jesus’ Israel, the Maccabean revolutionaries faced their deaths with courage and conviction. Since the death of Jesus, many of his followers have died for their faith in him with almost super-human bravery. Even in the pagan world, stories of dignified deaths (one thinks of Socrates) were told to inspire and fortify. And yet here is Jesus, overwhelmed by what is about to happen to him, pleading that he might be spared.

But rather than being an embarrassment, I think the scene in the garden of Gethsemane is a clue—a vital clue—for answering the question that is driving this book: “Why did Jesus die?”

Overwhelmed with sorrow

Then Jesus went with his disciples to a place called Gethsemane, and he said to them, “Sit here while I go over there and pray.” (Matt 26:36)

Jesus was a man of prayer. He prayed regularly, and he taught others to pray—most famously in the Lord’s Prayer. There’s nothing unusual in the thought that Jesus would now take time to pray. But events take an unusual turn. Taking his three closest friends with him, he becomes “overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death”, and he asks his friends to stay and keep watch with him (Matt 26:37–38). He’s not overwhelmed with sorrow at death—that is, at the thought that he is about to die. What he means is: “the sorrow I am carrying feels like it will kill me”. He feels as if he is being drowned by sorrow.

Some of us will have known a sorrow of this calibre. The sort of sorrow that feels like it’s swallowing you into the darkness. The sorrow that engulfs and suffocates. That feels like it is about to drag you under and into the grave. The claustrophobia of inescapable darkness. Jesus is saying he feels like that.

We’ve never seen Jesus like this before. They’ve never seen Jesus like this before. It must look to them (and it looks to us) as if Jesus is—and I don’t know how better to phrase this—not coping.

Do you remember the first time you saw your dad cry? This will depend a bit on the kind of family you came from and the kind of dad you had. But for lots of families, the whole point of dads is that they cope. When you’re a kid, dads just seem so strong. And by their strength, you gather the feeling that things are going to be okay, because he’s okay. But one day, you find your dad crying, or not coping, or diagnosed with something that will end his life. As a child, everything you think is true and makes this world safe and good is brought into question.

Something like that must be going on for the disciples. Jesus’ shoulder was the one they cried on. He’s the one who said to them, “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest” (Matt 11:28). He’s the one whose job it was to cope, so that they knew everything was going to be okay.

But now, the one who had told them time and time again “I’ve got this” is saying, “I haven’t got this. Stay here and keep watch with me” (see Matt 26:38). When he comes back to them, they’ve fallen asleep and he pleads with them, “Couldn’t you men keep watch with me for one hour?” (v 40). They had one job. And they couldn’t even be there for him in his greatest hour of need. Everything they thought was true, everything that made their world seem safe, was being brought into question.

The cup and the prayer

“My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me.” (Matt 26:39)

The focus of Jesus’ prayer is not a general prayer that he be saved from death, but a specific prayer that he be saved from drinking “the cup”. The cup is an Old Testament picture of God’s wrath. In the book of Isaiah, for example, the prophet is declaring that judgement is coming on Jerusalem for her sins. Note the language:

Awake, awake! Rise up, Jerusalem, you who have drunk from the hand of the Lord the cup of his wrath … (Isa 51:17)

Do you see? Here is the difference between Jesus and Socrates, Jesus and the martyrs, Jesus and those who would die in his name after him. They looked to their deaths and saw pain, suffering and costly faithfulness. But Jesus alone looked toward his death and saw all the sin and guilt of man, all the weight of God’s holy anger against violence, unfaithfulness, injustice, perversion, cruelty, inhumanity and unholiness. All of that was what he was about to experience in his death. That was the cup he was to drink.

When you understand the meaning of the cup, the prayer of Jesus in the Garden is not embarrassing. It is extraordinary.

For one thing, it’s a prayer. This is not Jesus talking to someone else about God. This is Jesus talking to God, to his Father, about the cup. There is an enormous difference between complaining about God and complaining to God. Complaining about God in the Bible is always faithless, disobedient, wicked. But the Bible’s solution to complaining about God is not a stiff upper lip and a “mustn’t grumble” attitude. It is, rather, to take our complaints about God and address them to God, to ask God to consider our lament (see Ps 5:1). This is what the Lord Jesus does here.

Notice also the form of the prayer: “My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me”. The prayer places no conditions on God; it contains no threat of disobedience. It is not an “if/then” prayer—“Father, if you take this cup from me, then I will [insert lavish offer of obedience here]”. He submits himself to the will of his Father, resolved to drink the cup that you and I deserve. The battle was won on the cross because the battle was won in the Garden. Going on from there was the bravest thing he ever did.

* JRR Tolkien, The Hobbit: Or there and back again, Unwin, 1981, p 205.